India’s new coastal law threatens Mumbai’s ancient fishing villages

At the end of the monsoon rains every year, Mumbai's fishing community perform a traditional religious ceremony to mark their return to the sea, with offerings of coconuts and flowers, and prayers for safety and bounty.

This week, as they launched their freshly painted boats into the water, there was an added prayer: the preservation of their homes and livelihoods as a new coastal law threatens them.

Changes to India's Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) rules this year have lifted the ban on land reclamation for commercial purposes, will allow tourism in ecologically sensitive coastal areas and permit construction of the world's tallest statue on an artificial island near Mumbai.

The fishermen - known as kolis - say the changes will lead to environmental damage, displace coastal communities and hurt the livelihoods of millions who depend on the sea for their survival.

"The coastal lands are ours by tradition. The state plans to take them away with this law," said Rajhans Tapke, general secretary of the Koli Mahasangh association.

"Our land will be lost, our access to the sea will be affected, our catch will be affected. How will we live?" said Tapke, who lives in Versova koliwada, or fishing village, home to his family for generations.

The kolis are among the city's earliest inhabitants, with settlements dating back more than 400 years.

The name Mumbai is believed to derive from Mumba devi, patron deity of the kolis.

Yet most kolis do not have titles to their homes or the land on which they spread their nets and dry their catch.

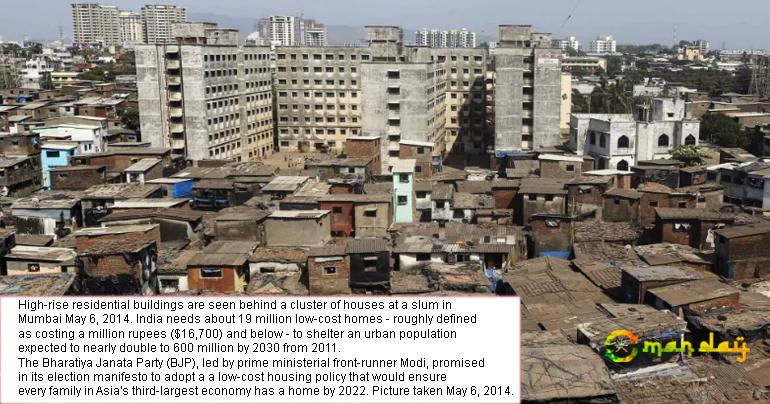

Versova is one of nearly 40 koliwadas in Mumbai, its squat homes and colourful boats dwarfed by towering apartment blocks and malls in the city which boasts some of the priciest real estate in the world.

City officials have long clashed with the kolis' right of use of coastal land.

The kolis, whose song and dance are part of Mumbai tradition and who have featured in Bollywood movies, have lost swathes of land over the years to railway stations, schools and parks.

They have resisted attempts by city officials to classify their settlements as slums, so they can be redeveloped with some land taken for commercial developments.

"Use of coastal land has always been tenuous, with the state pushing against people who have traditional land-use rights," said Manju Menon, a senior fellow at the Centre for Policy Research, a think tank in Delhi.

"In an urban area like Mumbai, with competing interests of the tourism and real estate industries, it is particularly contentious," she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. India's coastline is more than 7,500 km (4,660 miles) long, and about 3.5 million people make a living from fishing and related activities.

There are more than 3,000 fishing villages along the coast, from remote rural hamlets to bustling urban settlements in cities such as Mumbai and Chennai.

The set of rules regulating coastal development, known as the CRZ notification, was first issued in 1991.

The 2011 notification, which placed greater limitations on development, came about after consultations with kolis, and created coastal committees that also represented them.

Amendments to the notification this year, permitting reclamation of seabed land for coastal roads and tourism facilities, were made despite objections from fishing communities and environmentalists, analysts say. Kolis in Mumbai say they will be badly hit.

...[ Continue to next page ]

tag: international-news , legal

Share This Post